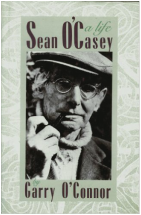

As a biographer of the Irish playwright Sean O'Casey I cannot help thinking how similar in many ways he was to the present leader of the Labour Party. O'Casey was described by his publisher and lifelong friend Harold Macmillan as a saintly kind of man, who thought "everyone ought to be equal out of kindness". He was a very strong Irish Republican, who engaged in the 1917 uprising, the subject of which formed some of his best plays, and subsequently he settled in England, and was a close friend and supporter of Bernard Shaw.

Nevertheless, while maintaining his style of dressing always in rollneck sweaters and skullcaps he maintained relations with the highest in the land, and presented himself as a lover of mankind who took to heart the aspirations of poor and needy, and was against any kind of capitalist exploitation. Now you might have thought from reading his wonderful early plays Juno and the Peacock and Shadow of a Gunmen, and his outpourings of love and compassion to mankind and his three children, that he could never end up believing and supporting mass terror and extreme totalitarian repression.

In my next post I refer to a particular case which I feel should strongly be related to that of Jeremy Corbyn and wielding power over the minds and hearts of his Labour supporters in our society.

For Part 2 look out for my weekly posting.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed